This is Part 3 of an 8-part series about Adrenal Fatigue (HPA-Axis Dysregulation), how it relates to your health, how to know if it’s impacting you, and what you can do to fix it! Click here to read Part 1 and Part 2.

In the Parts 1 and 2, we talked about how adrenal fatigue (HPA-D) feels, and associated symptoms and disease states. But what is actually going on in our body when we experience stress, that leads to these changes and symptoms?

(warning: this post gets a bit more technical, so read on if you’re curious…or skip it and click here to get support)

How Your Adrenals and HPA-axis Work:

You are planting a garden outside of your hut, when a hungry bear and her 3 cubs stroll out of the forest. You know a hungry momma bear is not to be messed with.Your brain goes into“high alert” and, in a split second, you decide to run.

The shift into Fight-or-flight mode occurs because your brain perceives some type of danger or stressor.

This decision took you less than 2 seconds, but in that time, a complex chain of events occurred before you were able to get into Go-mode:

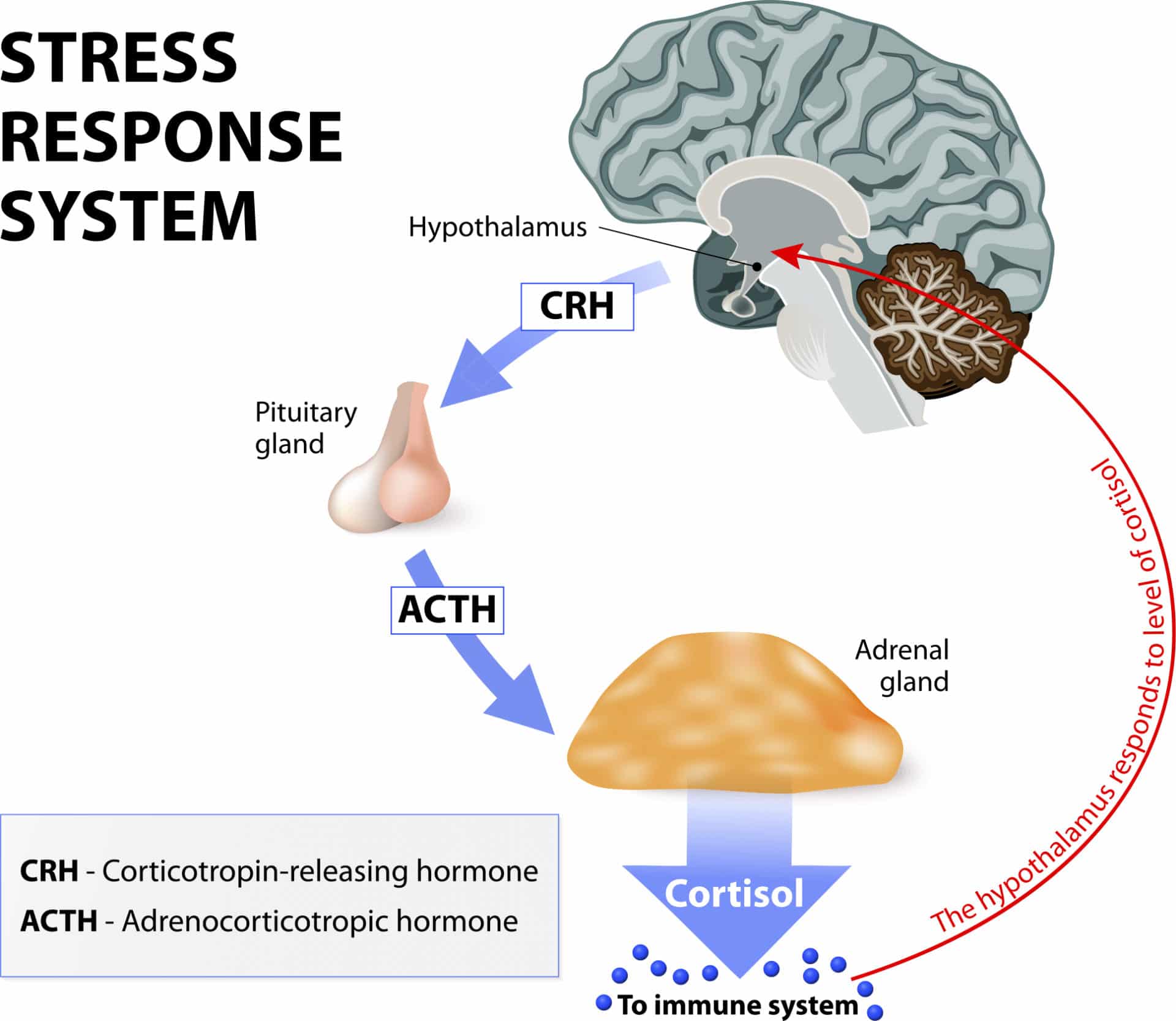

In a big game of physiological telephone, stress registers in the brain, where your hypothalamus signals the pituitary, which then signals the adrenals.

The adrenals release hormones into the blood stream that make their way to the brain. This is the negative feedback loop that lets the hypothalamus and pituitary know the message has been received and the job performed.

Depending on whether the brain is perceiving the level to be high enough to meet the demands of the stress, it will keep signaling the adrenals to produce more cortisol, or stop sending the hormonal signal so that the gland will know it has put out enough.

The stress response happens in 2 phases: First, we release catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) that prime your body to act immediately. Secondarily, these chemicals trigger a series of neurochemical processes that tell the adrenals, “It’s go time!”, meaning, please make some cortisol–NOW!

Cortisol’s main role here is to increase your heart rate and therefore blood flow to your arms and legs, for running. It also mobilizes glucose to fuel the action.

The flood of cortisol helps to increase your breathing rate, initiate sweating, dilate pupils. It also shuts down movement in your digestive tract, to make sure our muscles have enough fuel to run from the bear, remain alert and keep our bodies cool, among other things. The overall effect is to prioritize energy to the Central Nervous System, Cardiovascular, and musculo-skeletal systems, which are critical to survival in a life threatening situation.

The rest of the body’s systems, such as digestion and reproduction, which are more essential for long-term survival are temporarily reduced in activity.

Priming your body to go into fight-or-flight when under duress is just one of the many hats that Cortisol wears. Cortisol receptors are found on almost every cell in the body—that’s how critical it is to almost every aspect of our metabolism.

Modern Stress

Our bodies were designed to survive and even thrive in situations that are stressful in the short term. For most of our lives as a species, this might have looked like the situation above. It might have been caused by something equally stressful, like falling into a river and having to swim to shore. In situations like these, increased levels of cortisol and adrenaline produce the perfect physiological response to help save your life.

But in our modern industrialized world, we are exposed to a constant barrage of ongoing, sub-acute stress throughout the day. Fighting traffic, meeting work deadlines, parenting issues, relationship glitches, the mortgage, the bills, taxes, and an endless influx of text messages, phone calls, emails, and social media alerts, each add to our stress.

Then there are the stresses that don’t always feel immediately stressful, but that add to our overall stress levels in more subtle ways. These include: sitting all day, lack of exercise, overtraining without enough recovery time, skipping breakfast in favor of coffee, eating processed foods, staying up late to watch one more TV episode, or exposure to lots of artificial light after sunset.

When the stress state is prolonged, cortisol is maintained at higher than normal levels for extended periods of time. Excessive exposure to cortisol actually causes a catabolic metabolic—this causes body tissue breakdown, as opposed to growth and repair. High cortisol levels in the brain permanently burn-out nerve cells in our hippocampus, our center of emotion and memory. So, when stress is too intense, or goes on for too long, our brain down-regulates the production of cortisol, in a disrupted feedback loop.

This is why “Adrenal Fatigue” is more accurately described by the term “HPA-Axis Dysregulation” (Hypothalmus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis). As the HPA-Axis dysregulation progresses, cortisol production often drops lower and lower, as does the production of other adrenal steroid hormones like DHEA.

Adrenal fatigue is actually a brain problem

When we talk about “adrenal fatigue” and “adrenal repair”, it can give the impression that something is wrong or damaged in the adrenal glands themselves. But issues stemming directly from the adrenal glands are truly only at hand in specific medically diagnosed disease states like Cushings or Addisons diseases.

A more accurate description of what adrenal fatigue really is, is the term HPA-Axis Dysfunction (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal dysfunction….say that 3 times fast!). This term describes the breakdown of the communication systems that these three glands use to talk to each other and regulate hormone production and rhythm every day.

The HPA Axis is our central stress response system. When your brain perceives that there is either something stressful or threatening in your environment (or if emotions run high), or if your blood glucose levels get low, or if you have high levels of inflammation, the hypothalamus shouts at the pituitary to do something about it. The pituitary in turn, signals the adrenal glands (by releasing a hormone called ACTH) to crank up the production line on cortisol, to help deal with the situation.

Normally, when the “stressor” is gone, the signaling quiets down, and cortisol levels should return to normal. But if the stress/inflammation/glucose problem is ongoing or severe, sometimes, the levels either stay high, or, alternately, shut down.

When you experience symptoms like fatigue, anxiety, insomnia, or foggy-brain due to imbalanced cortisol levels, it’s because of a breakdown in the signaling from the brain to your adrenal glands. In other words, the problem is in the software or programming, not in the hardware!

When we test with cutting-edge labs, and create treatment protocols, our aim is to reset the rhythm of the output of adrenal hormones. This process is dependent on restoring the feedback loops between the control centers in the brain.

After long term stress or inflammation, we adopt a new normal. Treatment to restore balance is a bit like restarting the computer and rebooting the software.

To learn more about how stress and adrenal hormone dysregulation can throw a wrench in your sex hormone balance (like estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone), continue on to Part 4.

At the Reverse-Age Method, we believe in a holistic approach to perimenopause and beyond, that addresses the root causes of your symptoms (like insomnia, hot flashes, night sweats, erratic periods, fatigue, skin aging, weight gain, and brain fog)– to also slow the pace that your cells are aging. Whether it’s improving gut health, optimizing detox function, enhancing mitochondrial function, or building muscle mass, our comprehensive program has got you covered.

If you’re new here, be sure to check out our Blog Page for more insights and tips on how to thrive during perimenopause. Our blog is packed with practical advice, success stories, and the latest research to help you on your journey.

For more updates and community support, follow us on social media:

You May Also Like...

How to Heal Ulcerative Colitis: A Case Study

If you have ulcerative colitis, this is a case study you’re going to want to read. It’s about a woman—I’ll call her…

How to Prevent SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth) Relapse

You have SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth) and you completed all the necessary steps in the “kill phase” of…

Whether you’re looking for help with your gut, your hormones, or both, our team of practitioners work together to treat the WHOLE you – guiding you to a healthier mind, body, and spirit day by day.